If Fatu and Sudan had a choice, would they have delegated the birthing of their baby to another female?

The idea of having a third female carry a couple’s child may still sound unusual to many. However surrogacy, or the arrangement through which a woman agrees to birth a couple’s baby, has long existed. The first account of it appears in Genesis. Abraham’s wife Sarah turned to her servant Hagar to be the mother of her husband’s child. Hagar thus played the role of a traditional surrogate where the pregnant woman provides the egg and is inseminated by the intended father’s sperm.

You expected this article to be about endangered animals and their conservation, so what does human surrogacy have to do with it and who are Fatu and Sudan, anyway?

Fatu is a northern white rhino, and together with her daughter, Najin, they are the last two northern white rhinoceros on Earth. This magnificent ancient species had been walking Earth peacefully for over 10,000 years. They endured changes in seasons, climate and nature, yet these mammals were defenceless against humans’ cruelty and greed after decades of poaching and loss of habitat. Three species of rhinos are critically endangered, one near threatened, and one vulnerable. After the death of Sudan, the last male in 2018, the extinction of northern white rhinoceros became only a matter of time.

Now is our last chance to help birth them back.

Luckily, scientists have conserved semen of deceased northern male white rhinos but neither Najin nor Fatu are physically capable of carrying an embryo to term. So our best shot at trying to save their species is surrogacy.

Scientists have been exploring species conservation through human-fertility techniques since the 1990s. In June 2019, Prof. Hildebrandt and his team in Germany launched BioRescue, an ambitious project that uses state-of-the-art reproduction and stem cell technology as a last chance to save the rhinos. The project received €4 million from the German government as part of a biodiversity conservation initiative.

However, the anatomy of the rhinoceros’ reproductive system makes this task incredibly delicate. Because the team does not have the comforting luxury of trial and error, they used the southern white rhinos as their “lab rats”. Southern whites are closely related to their northern cousins and are good candidates for assisting in the survival of the endangered animals since they, themselves, are not at risk of extinction—yet.

Scientists harvested eggs from 14 southern females, none of which experienced any complications. The next milestone was achieved in May 2019 when they successfully transferred a test embryo into the uterus of a southern white female rhino.

In August, scientists were finally ready to operate on Fatu and Najin. A multi-national effort involving a number of zoos, research institutions and conservancy groups succeeded at collecting eggs from the last two females in an unimaginably delicate procedure. The eggs were fertilised using the preserved sperm. In September two of Fatu’s eggs successfully developed into viable embryos at Avantea Laboratories in Cremona, Italy where they are preserved in liquid nitrogen for future transfer.

The embryos resulting from this in-vitro fertilisation will be transferred to a female southern white rhino in the near future who will be the surrogate mother of not only a northern white rhino, but also of our desperate attempt to preserve their species.

Even if the procedure succeeds, however, numerous challenges lay ahead. How will the continuation of the line be guaranteed with such a limited genetic pool?

BioRescue’s answer to that is stem cell technology. Stem cells are special cells with the unique ability to divide and generate new cell types. BioRescue aims to transform a non-reproductive cell such as a skin cell into a stem cell which can then become a specialised cell like an egg or sperm. The team hopes that this would allow a more sustainable and genetically healthy population of northern white rhinoceroses.

Yet again, a challenge remains which is arguably the most important: is the wild a viable place for baby northern white rhinos?

Scientists might borrow the uterus of a different species to birth endangered animals, but they can’t borrow another planet for them to live on. A surrogate mother would carry a child, but a couple will have to raise it.

Taking care of our home, and theirs, is a global responsibility that every human shares. We have to be conscious about our ecosystem in our daily behaviours from ditching single-use plastics, turning off the light to managing food waste and meat consumption. These actions might not seem as heroic as birthing a baby rhino, yet they matter as much. They’re small individually, but collectively can have tremendous impact.

Our efforts might turn out vain, but at least, we would have tried. We would have learned how to be better for the next endangered species. We would be able to tell Mother Earth “we did everything we could” when Fatu and Najin take their last breaths.

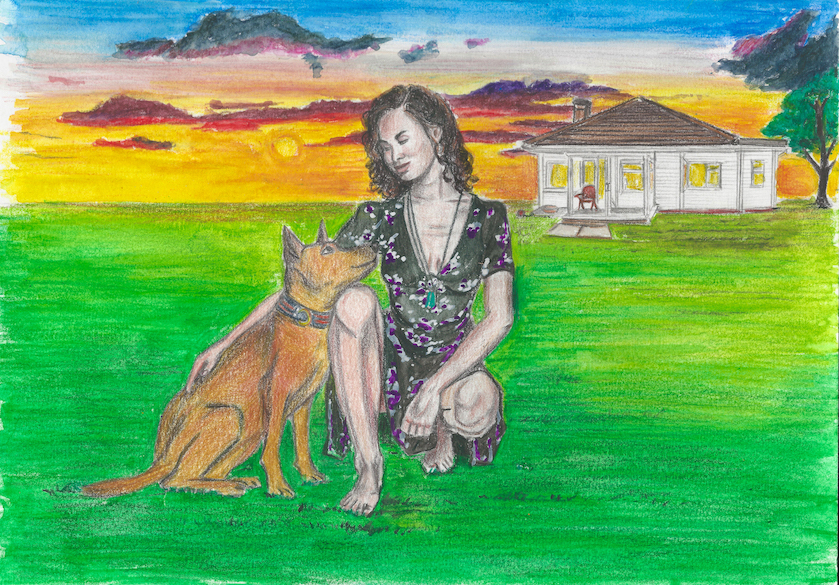

Artwork is by Helen Spence-Jones. The article was edited by Ghina M. Halabi.