Sputnik launched just as I started elementary school; the first astronauts landed on the moon soon after I finished high school. I watched the story of our first space age unfold on our old black-and-white Philco TV as CBS news anchorman Walter Cronkite deftly narrated events that held me enraptured. What kid growing up during this heady time wouldn’t want to be an astronaut? Sadly, girls of my era were not allowed, encouraged or academically prepared to pursue careers in science and tech. “You don’t have the right temperament,” my high school guidance counselor admonished me when I told him I wanted to take advanced trigonometry. He signed me up for an art class instead.

My art classes led to my first job after college, as art director in a small TV station, back when the news was still shot on film. I got free filmmaking instruction, all the 16mm filmstock I could squirrel out of their seemingly unlimited supply, and free processing. I learned to shoot and edit film, conduct an interview and cover a news story. I also learned about sexism in the workplace, and about my legal right to sue my employer for discriminatory practices, but that’s another story.

I could complain about missing out on a career that might have put me squarely inside a spacesuit, like Valentina Tereshkova who in 1963 dashed my hopes of becoming the first woman astronaut. Now, however, I consider myself fortunate to have acquired filmmaking skills that equipped me to address women’s issues just as the feminist movement of the seventies gained steam. In my first short animation, Parthenogenesis, a female egg rejects a swarm of aggressive sperm and instead finds a way to self-reproduce. For my most recent film, Madame Mars, I spent four years finding and telling the stories of women whose study and exploration of Mars have not been part of the mainstream history of space science and tech. My goal, then and now, has been to create stories that contribute to an authentic, revisionist, feminist history.

In the story of the space age I was told as a girl, the emphasis was on the male astronaut hero, his quest to “conquer” space, and the can-do men in mission control who got him to the moon and back. Only recently have we begun to learn about women who were also integral to the effort, women who were there, but were not visible. Presence and visibility are two entirely different things; it’s how the story is told – and very often who tells it – that makes all the difference.

Recent books like Margot Lee Shetterly’s Hidden Figures and Nathalia Holt’s Rise of the Rocket Girls illuminate vital historical roles of females in space exploration. When we look at the broader story of women in science and tech, we find Dava Sobel’sThe Glass Universe. It’s the story of female astronomers who studied glass photographic plates of stars because they were not allowed to look through large telescopes used by men. Denise Kiernan’s The Girls of Atomic City tells the story of women who helped build the first atomic bombs, though they were never told what they were doing. Claire Evans’ Broad Band presents a rich and engaging account of women’s contributions to networked and computing technology. In her story, Evans argues that communities of women working collaboratively, and most often namelessly, have had the most formidable impact in science and tech arenas.

Because we are not going to Mars to visit, but ultimately to stay, we will need working communities with diverse skillsets. These skills will build and sustain settlements, nurture settlers, solve collective problems, and eventually raise families, and educate and prepare the next generation for tasks ahead. Women have decades of experience building and working in communities and thus are primed for this effort. The days of the astronaut hero are over. My own astronaut fantasy days are long past, but my commitment to advancing the roles of women in current and future space exploration has never waned.

We have a visibly diverse and global space culture now. Even as missions into deep space and to Mars will likely include explorers from multiple parts of the world, our media coverage requires a more diverse community to present stories of our future endeavours. Thankfully, media is no longer a one-way conduit with the single authoritative figure telling the story. Today’s storytellers represent all genders, colours and ages, and stories told using smart phones are shared instantly and globally via social media.

The first story told on Mars may inevitably be about that brave astronaut who takes the first iconic step. The stories that follow, however, will be about how we manage ourselves as humans living on another world, how those living on Earth interact with these first Martians, and how we all prepare ourselves for our myriad futures in an expanding universe.

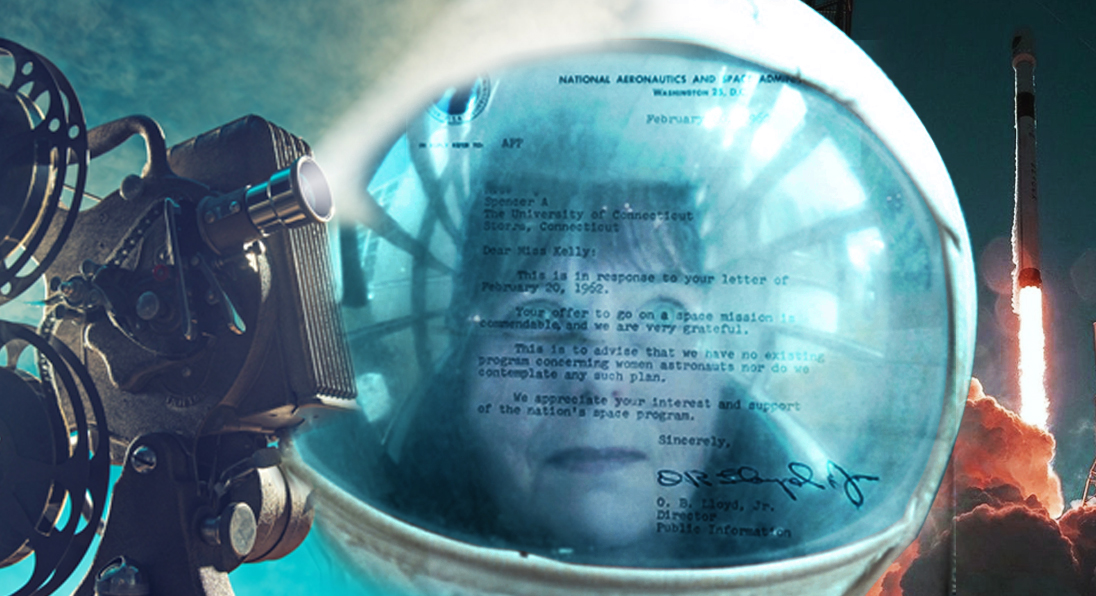

The image features a rejection letter by NASA to aspiring women astronauts in the sixties. Created by Ali Baydoun.